The Moral Dilemma of Being a Good Person on Instagram

Our recent shift toward Instagram activism asks a bold question: Is change still valuable if it comes as a side-effect of self-preservation?

We woke up that day as we always did: we opened our eyes, we opened our phones, we opened Instagram.

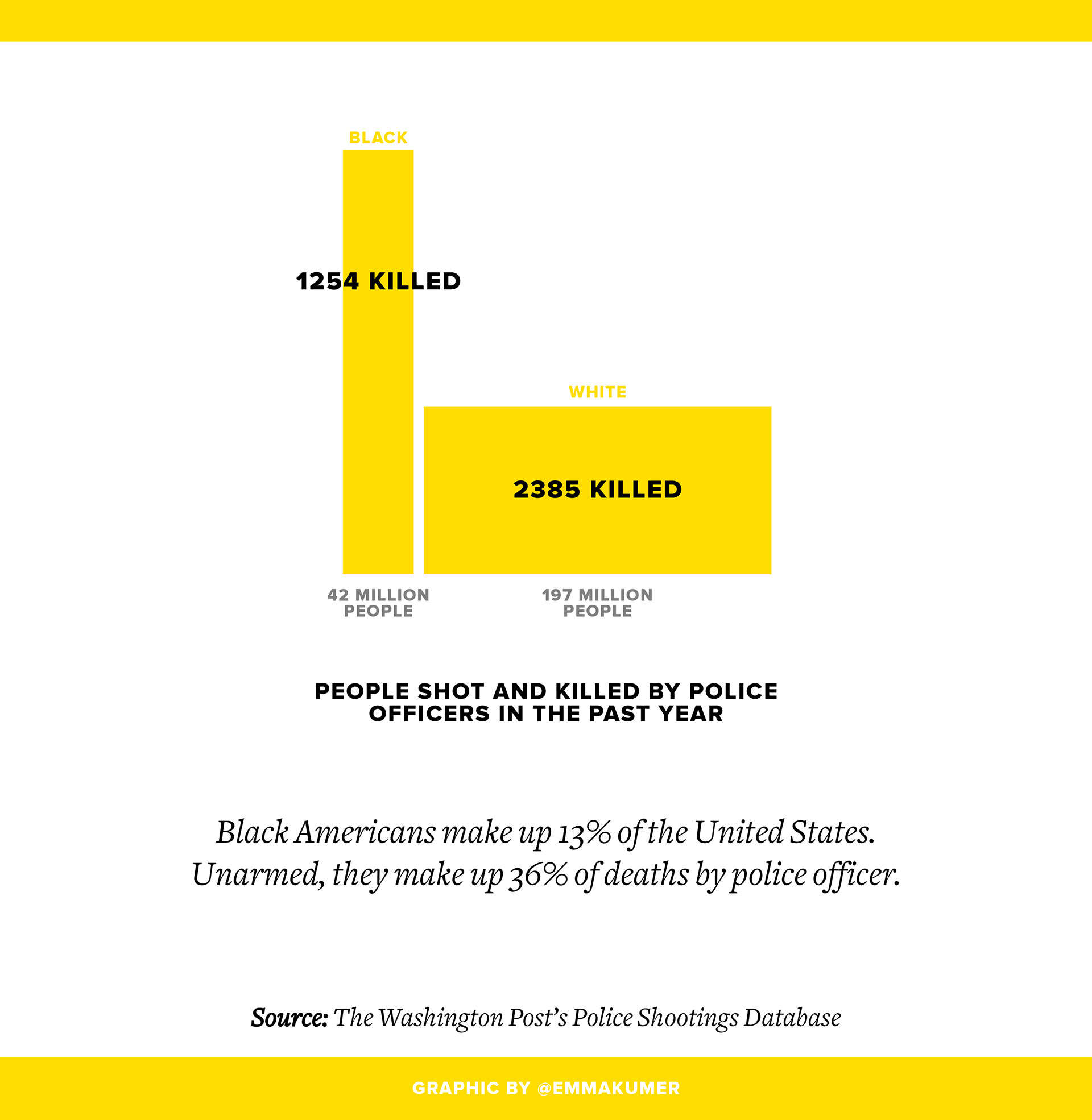

It was May 25, 2020, and we were met with the usual unharmonious choir of quarantine selfies and home workouts — until 10 a.m., when something abruptly changed. Some of us found out when we saw the video clip of a Minneapolis police officer kneeling on George Floyd’s neck until he died. Some of us were interrupted from our Monday emails by the alert that a 46-year-old Black father had been murdered by law enforcement. And some of us found out when Instagram became a procession of black squares, increasing as time passed, creating a wall between the before and after. For the first time in my memory, the digital world collectively decided to turn a platform of noise into a moment of silence.

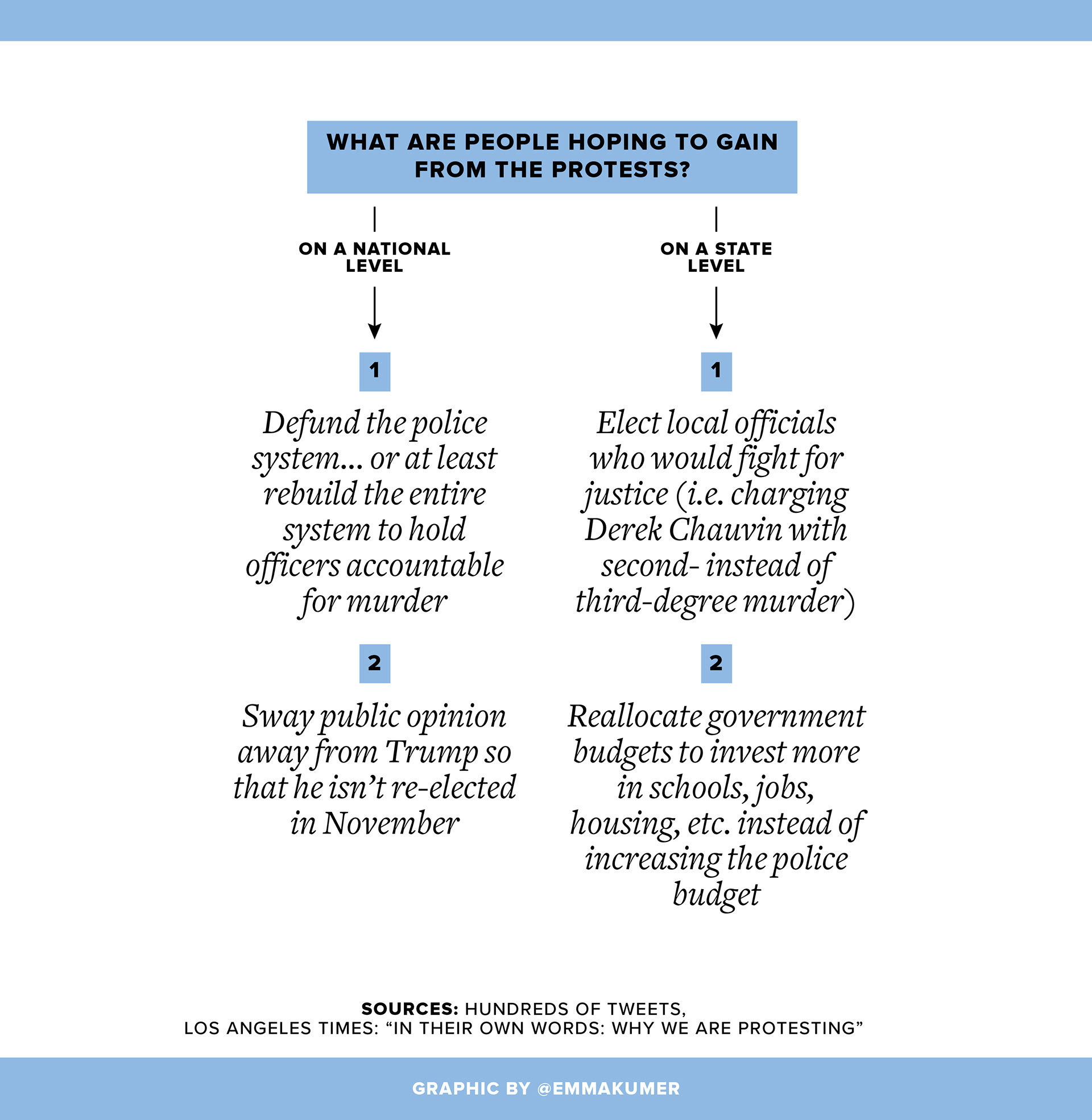

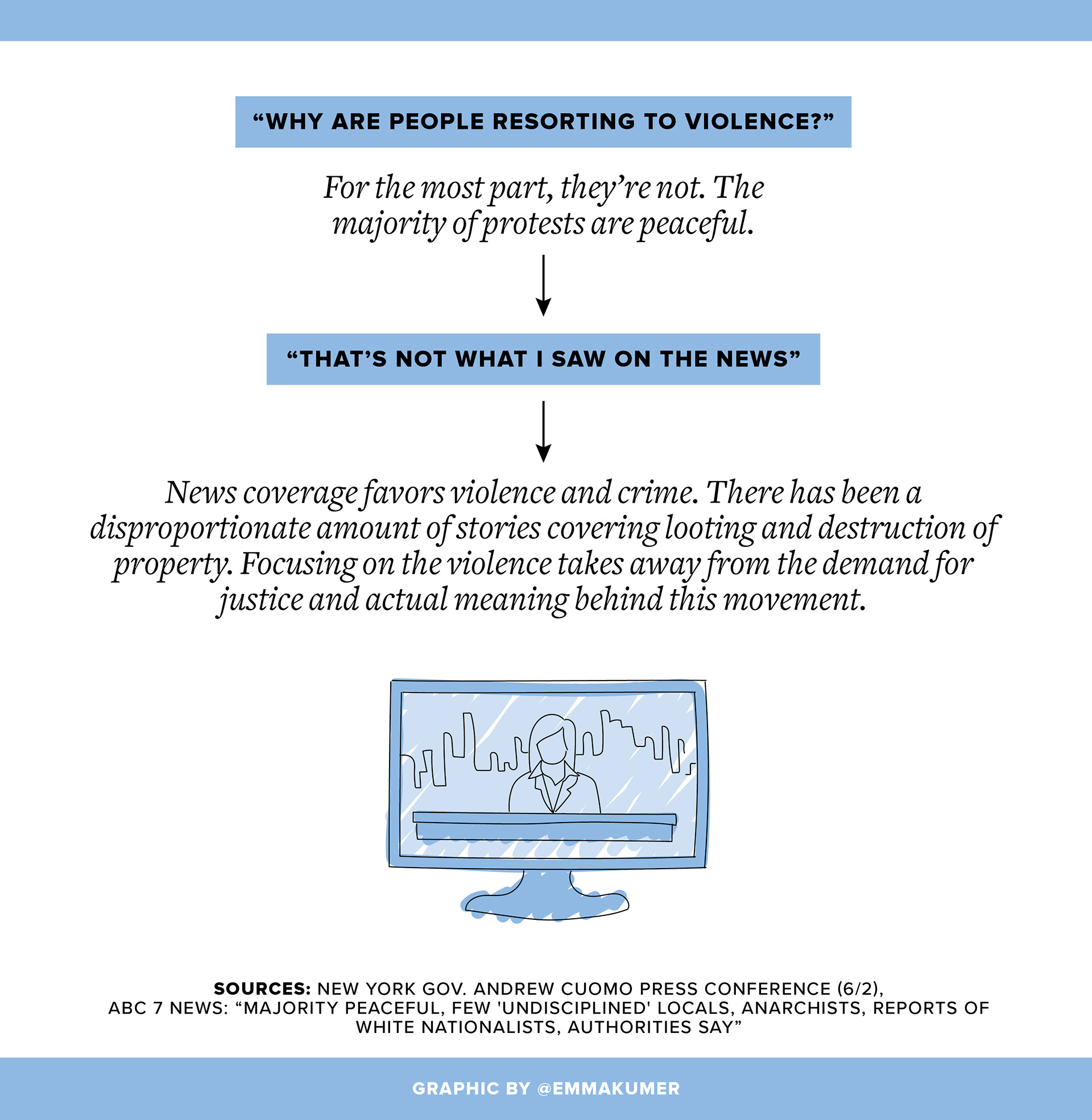

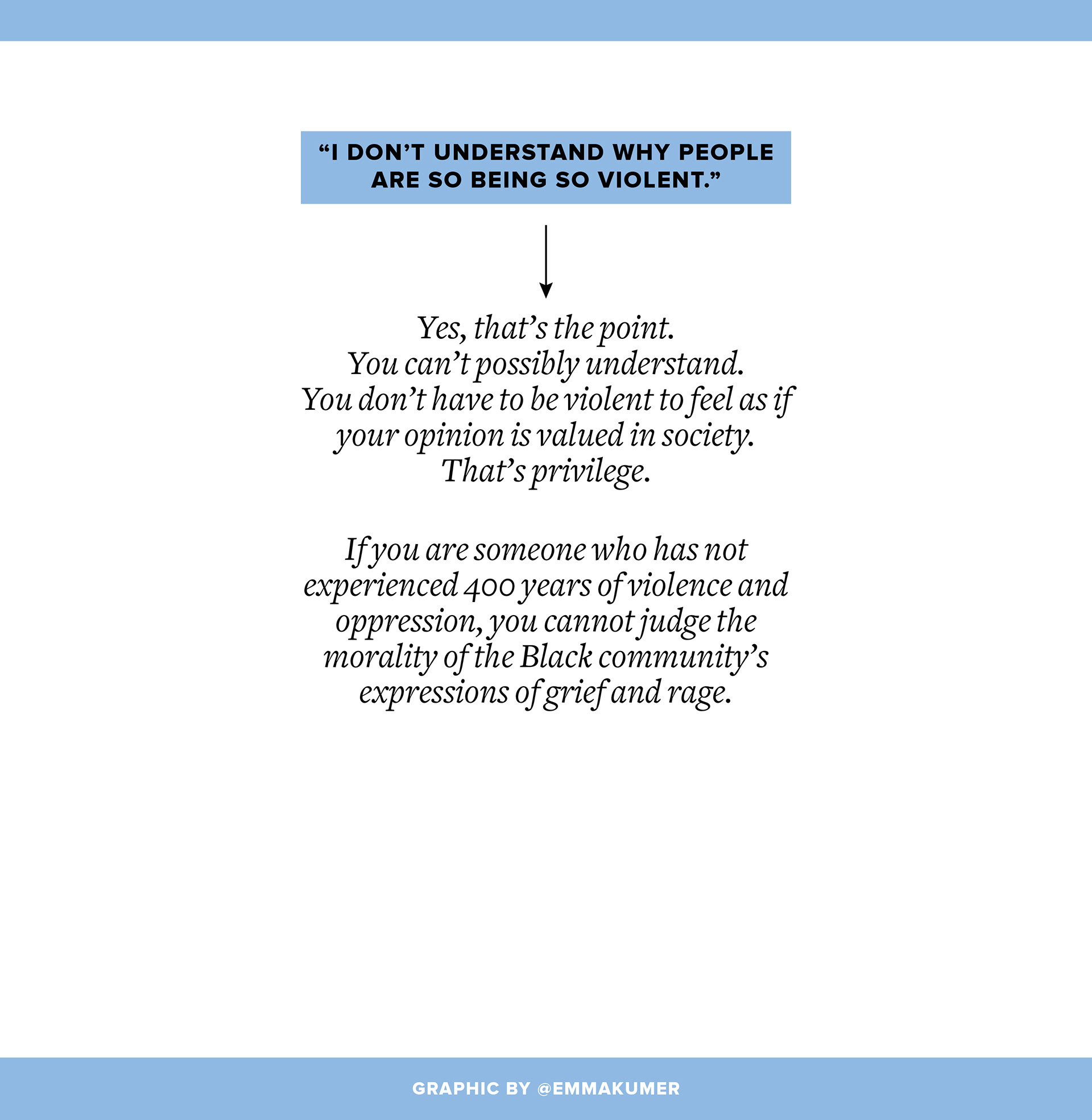

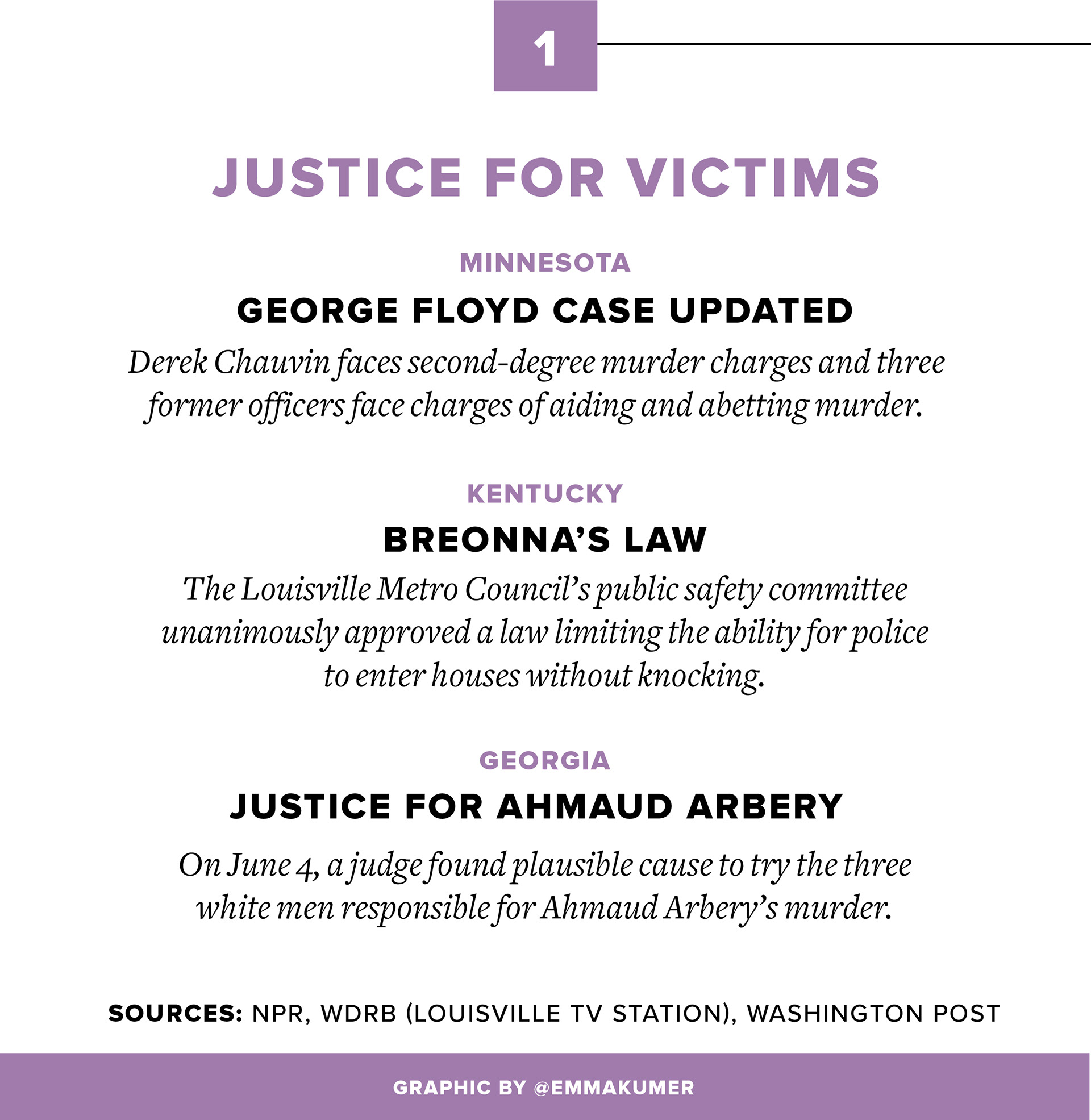

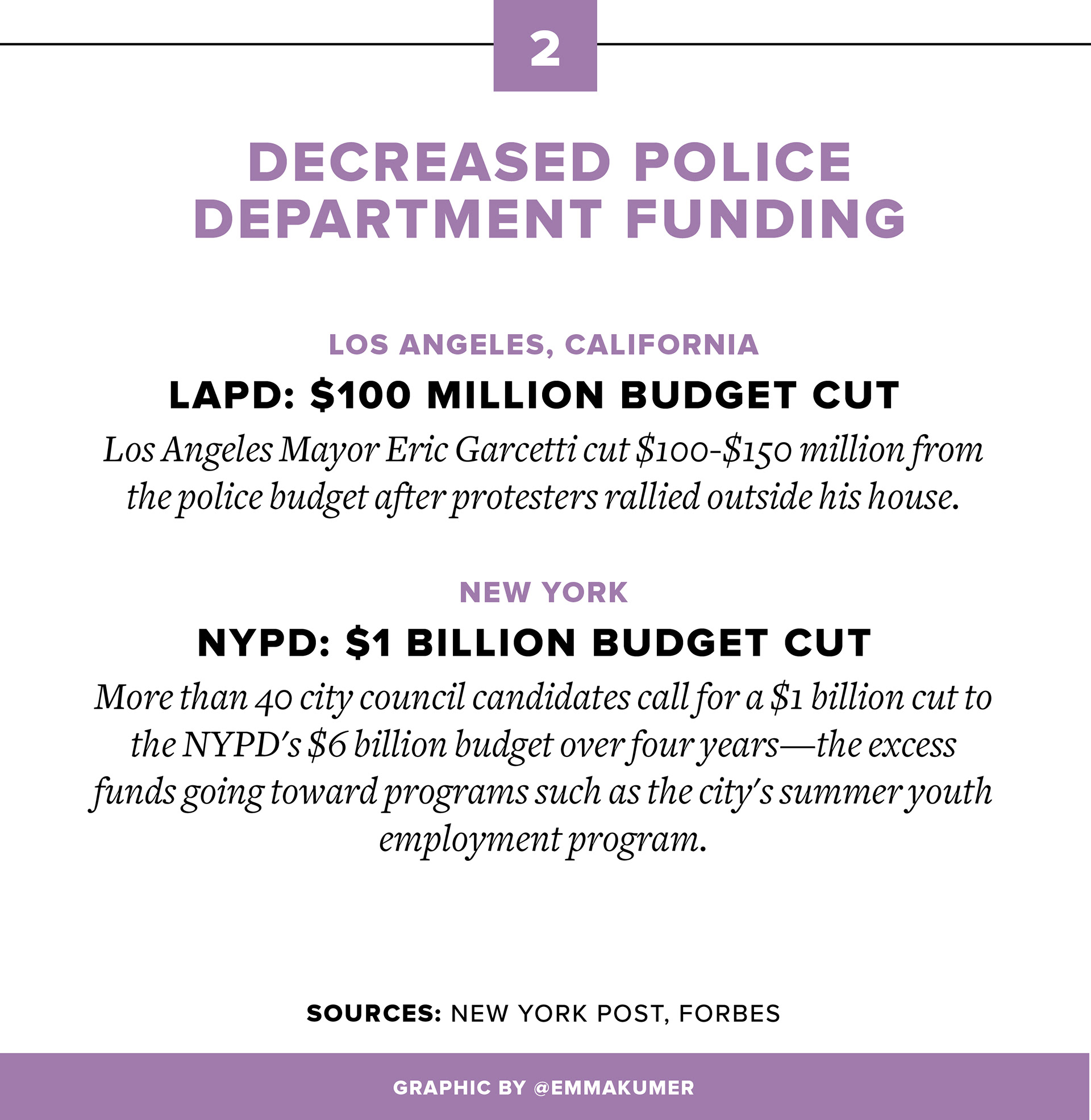

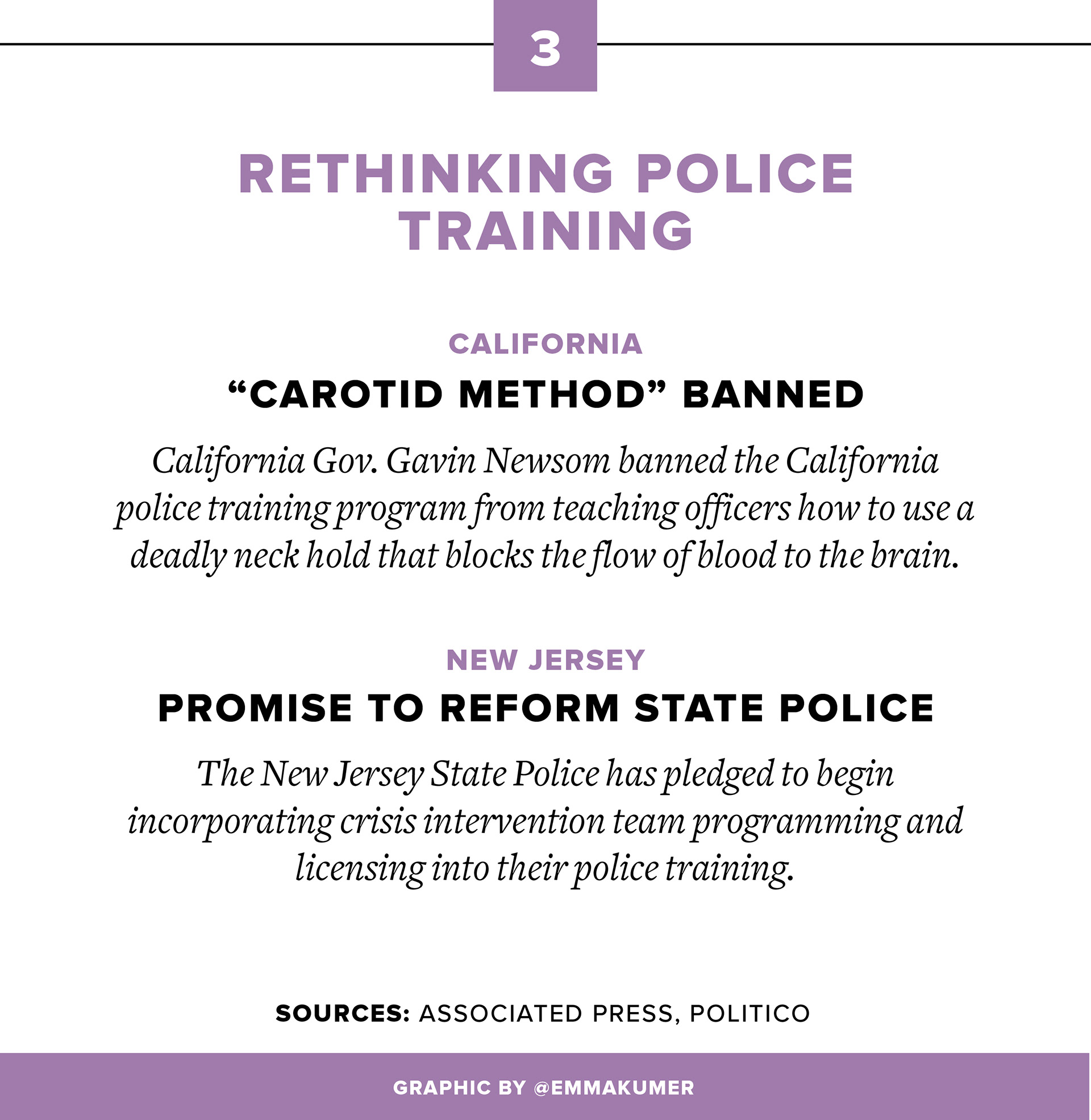

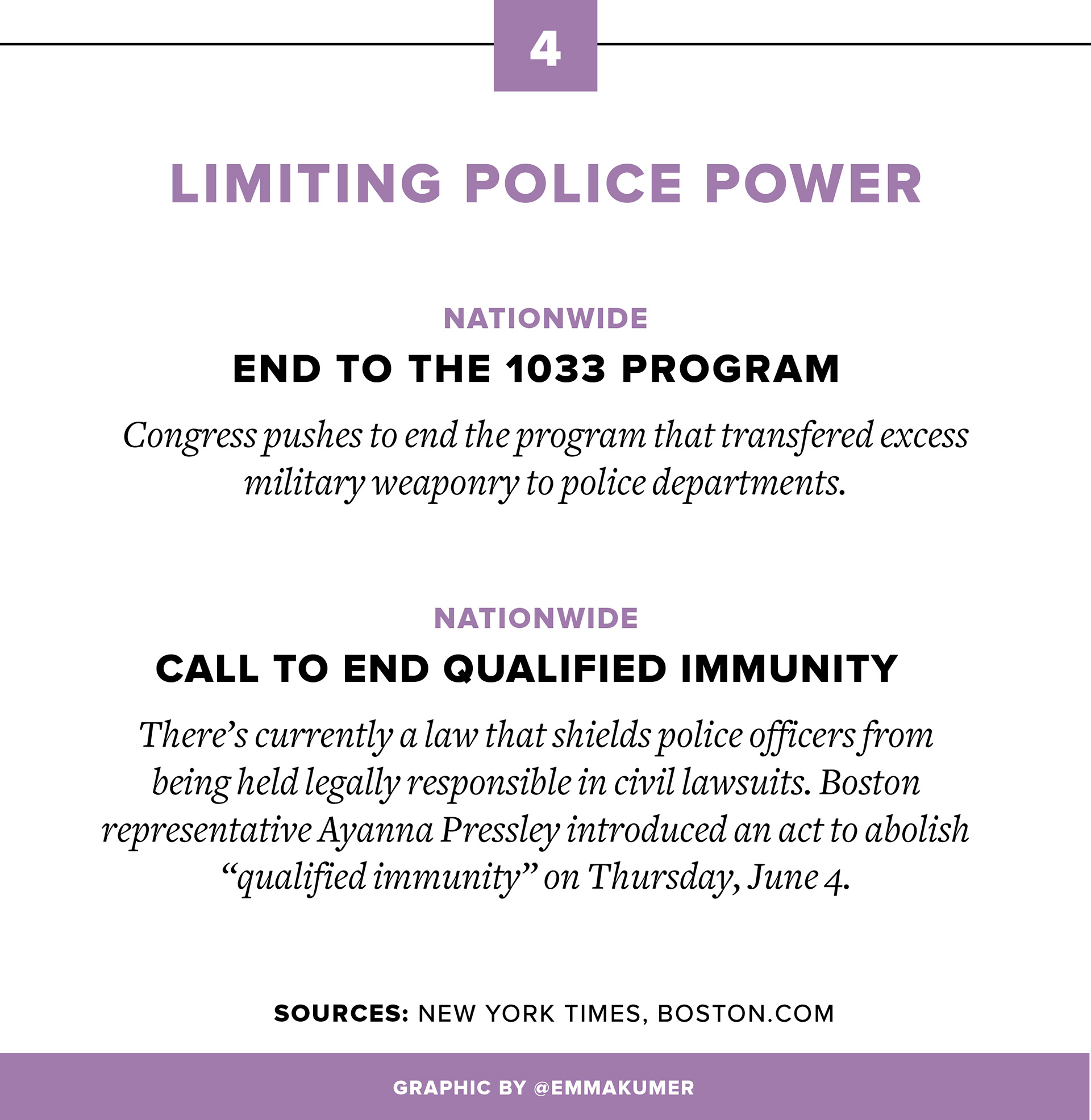

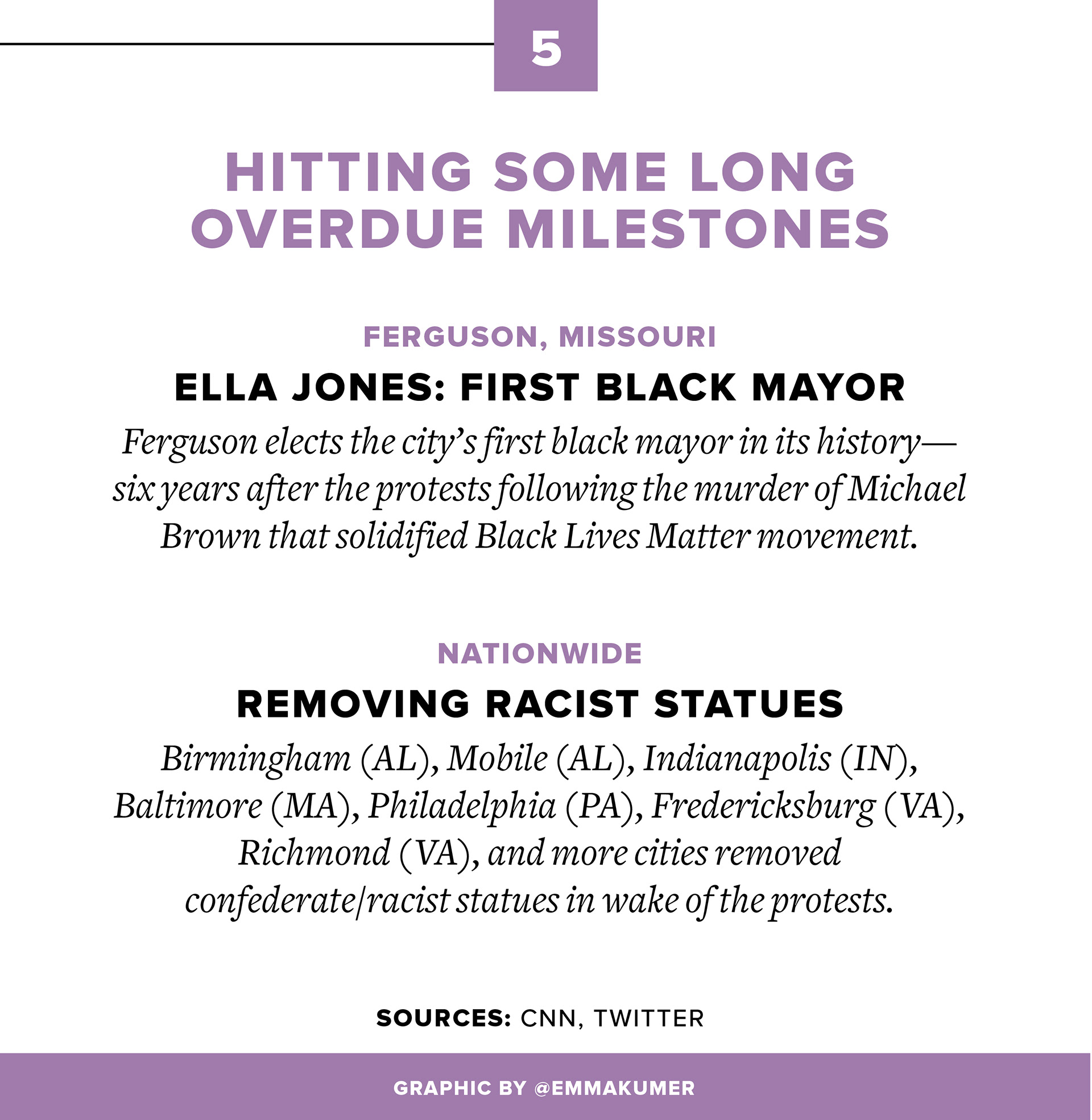

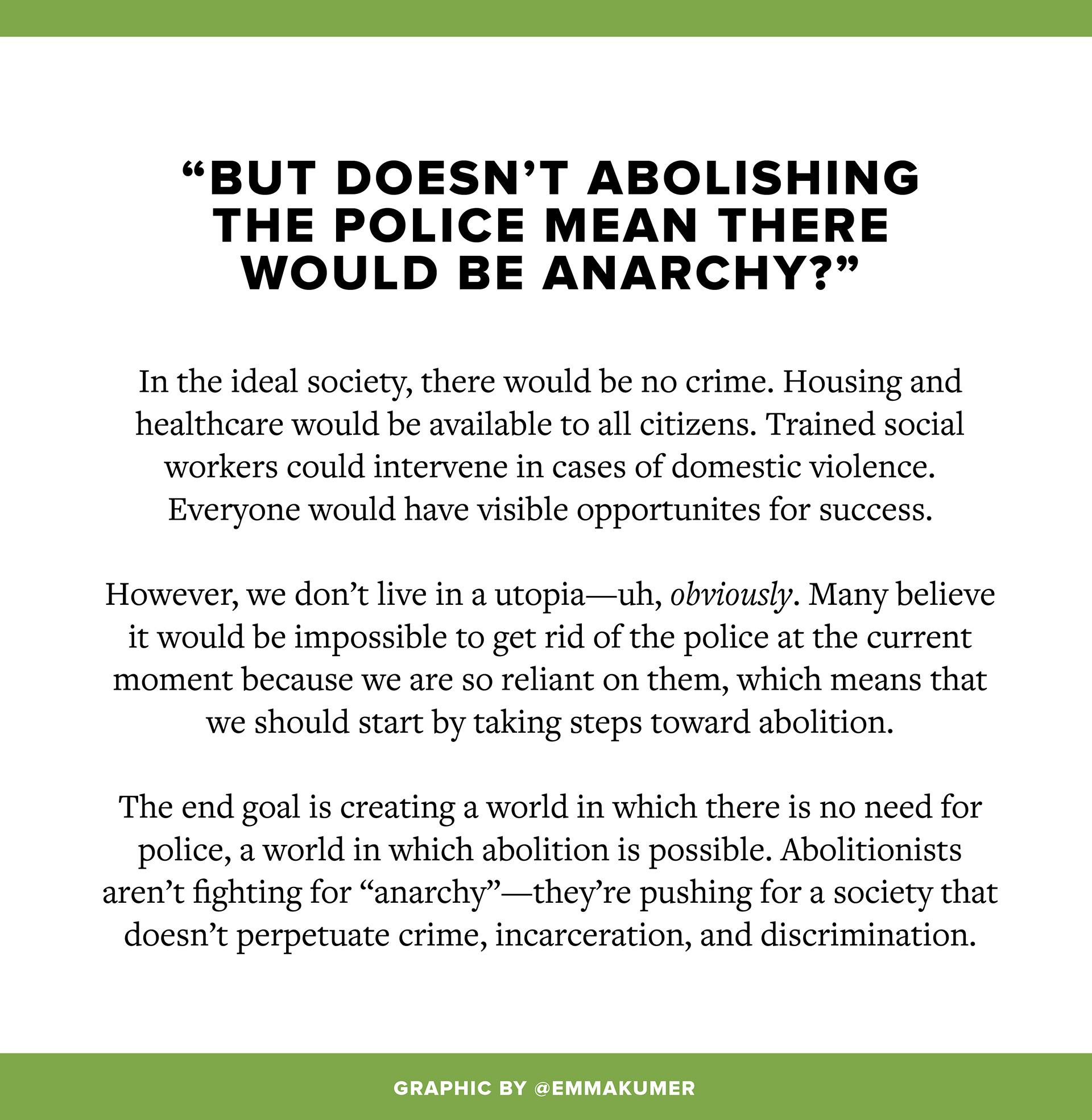

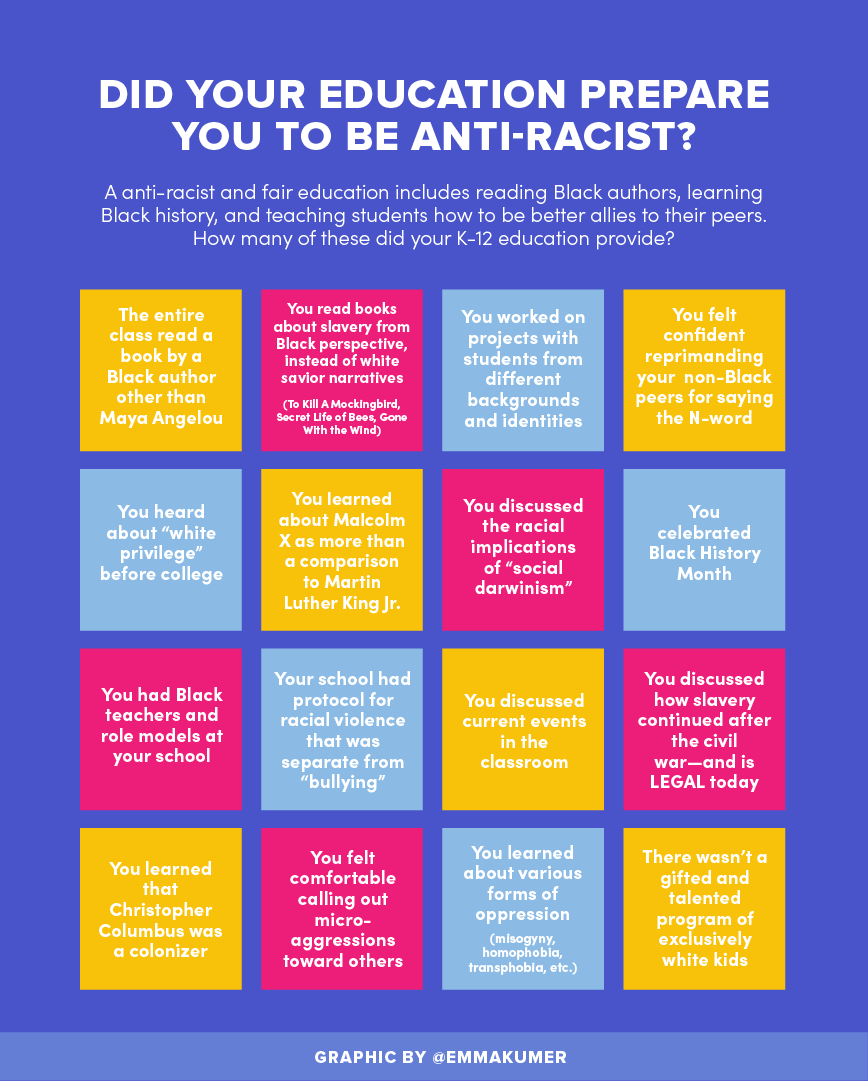

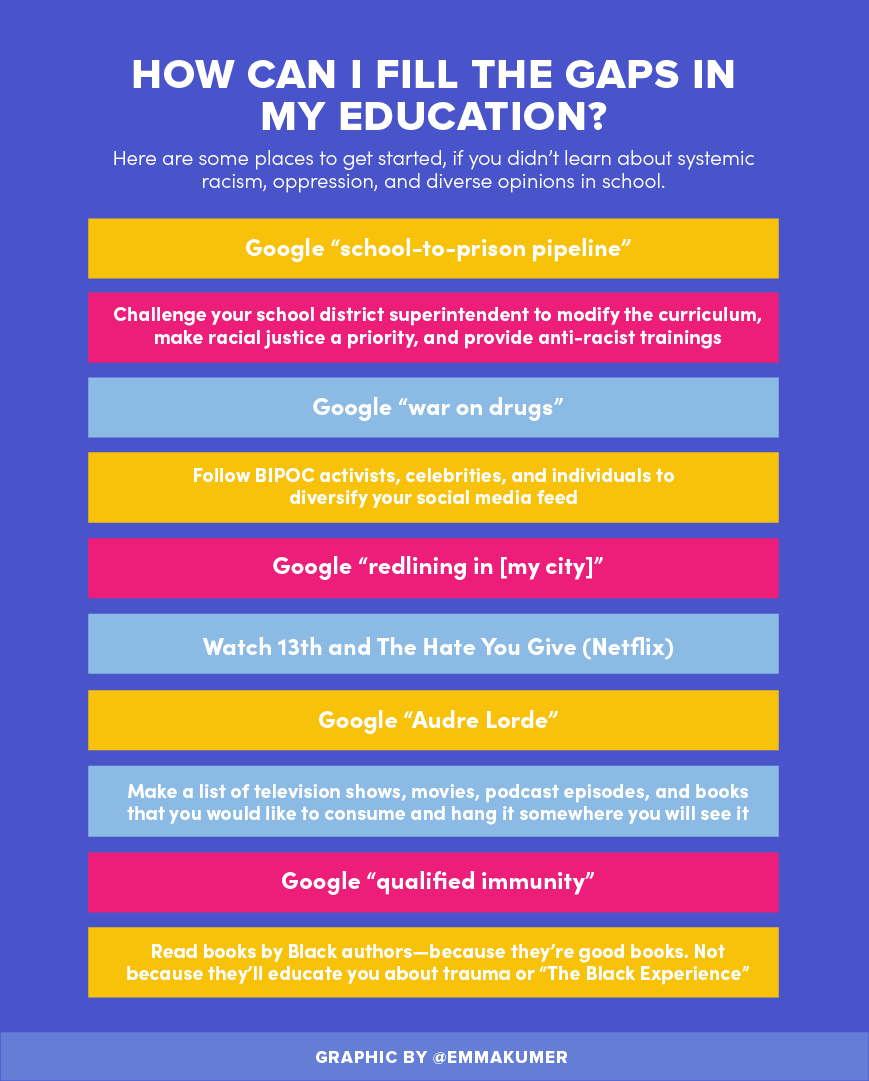

In contrast to the stark black squares of our feeds, Instagram stories became a different spectacle. This unending content stream, where the promise of its disappearance creates a sort of spontaneity, still buzzed with color and sound. In the coming weeks and months, everyone from my old college roommate to my middle school math teacher to Gigi Hadid was posting slideshow-style graphics aimed to help the sudden and fervent surge of the Black Lives Matter movement. These posts, later described by Vox as “powerpoint activism” and the general public as “Instagram Infographics,” came in a variety of topics. How can you educate your friends and family about BLM? Where are good places to donate? What are your rights as a protester? There was even one titled, “So, when can we post brunch pics again?”

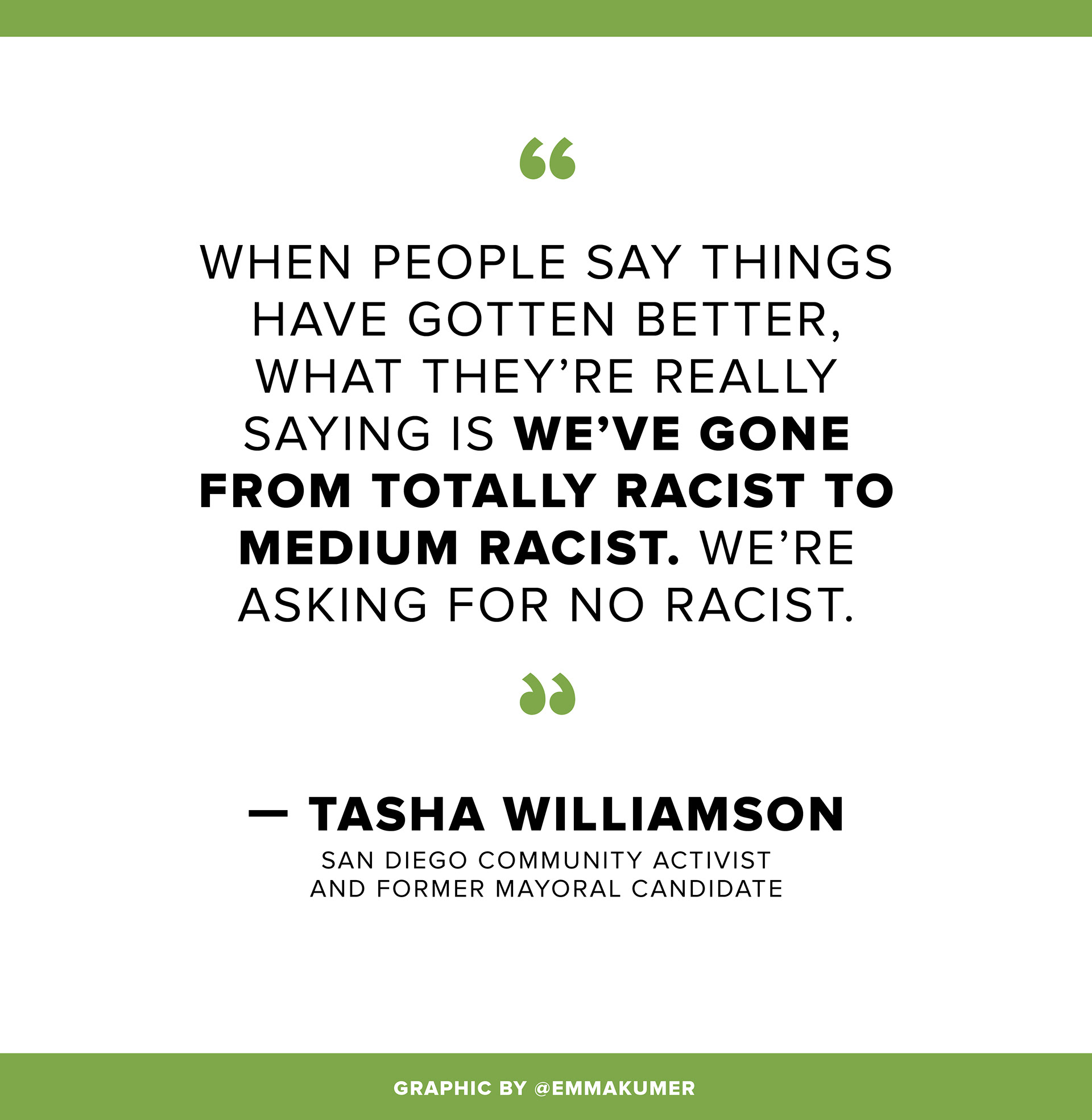

The infographics ranged in quality, typeface, and color. Some were detailed and prosaic, others snarky and loud. Some were created by large corporations and activist organizations, others by individuals with fire under their keyboards. Yet despite their diversity, they shared one uniting focus: The belief that Instagram could change the world.

The Dawn of Instagram Activism

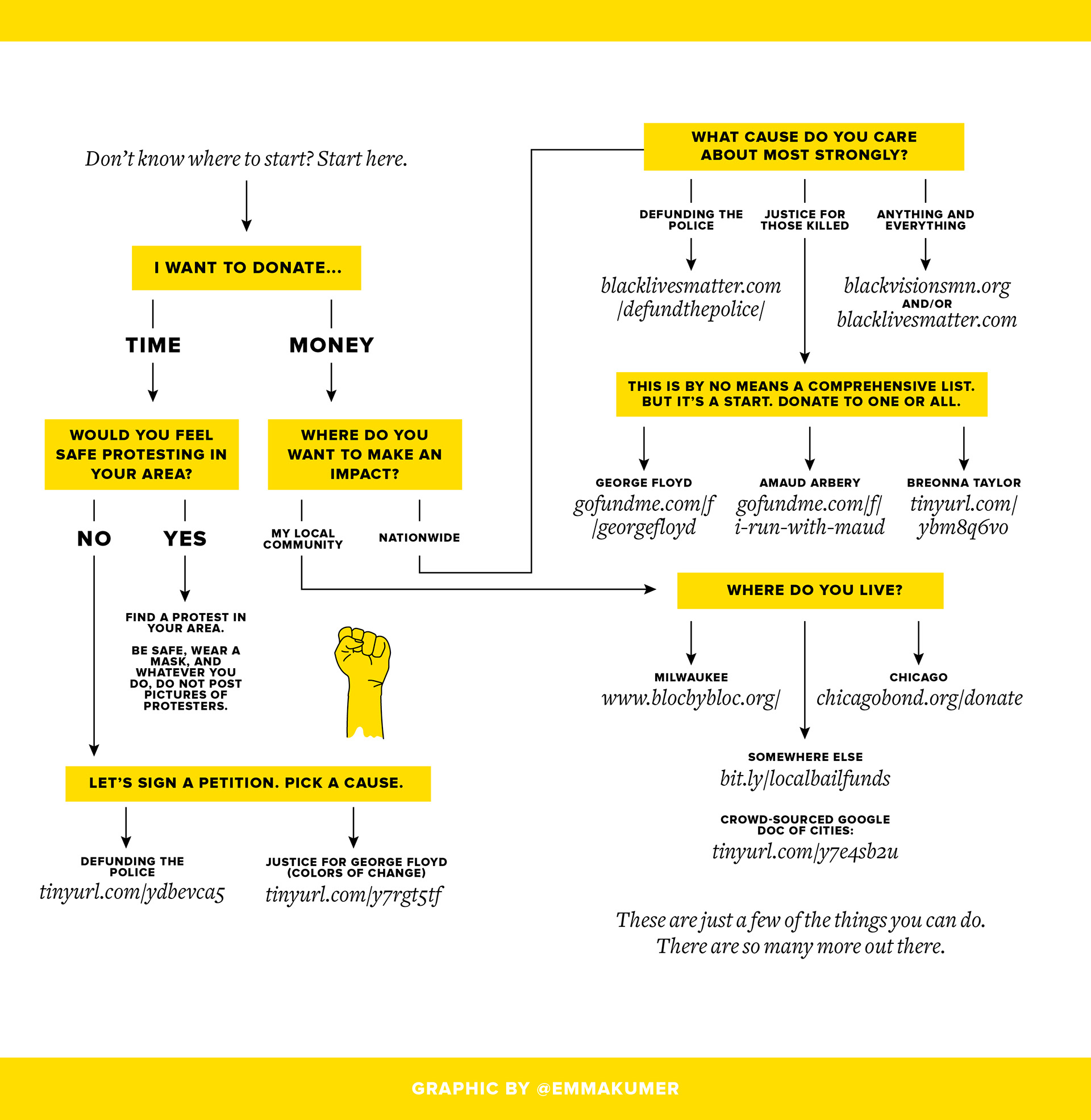

I fell victim to this hope, and to some extent, I am still under its spell. I published my first infographic on Instagram in complete oblivion of what was to come. I had created a flowchart of different places to donate and sign petitions, having gathered the links from the messy web of everything else I saw. Looking at the finished image, I thought my friends might find it helpful. Before I get any further, allow me to acknowledge that I’m also white; advocating for Black justice is on all of us. So, I posted. I had no idea it would go viral.

Instagram seemed hungry for this content, almost stunningly so. My post was viewed 100 thousand times and shared by twelve thousand. Some of my later infographic posts would reach an audience ten times as large. Beyond these numbers, though, it was impossible to track their effect on people. I had no way of knowing if people were reading through the entire post, using the donation links I had provided, or attending protests. To this day, this remains one of the silences in the argument surrounding Instagram infographics: no one knows if they do anything. You can’t track engagement IRL.

At this same time, I started seeing a few recurring names on my friends’ stories, like @eisellety and @wastefreemarie. Dedicated news and activism accounts like @soyouwanttotalkabout (now @so.informed) and @shityoushouldcareabout noticed meteoric follower gain.

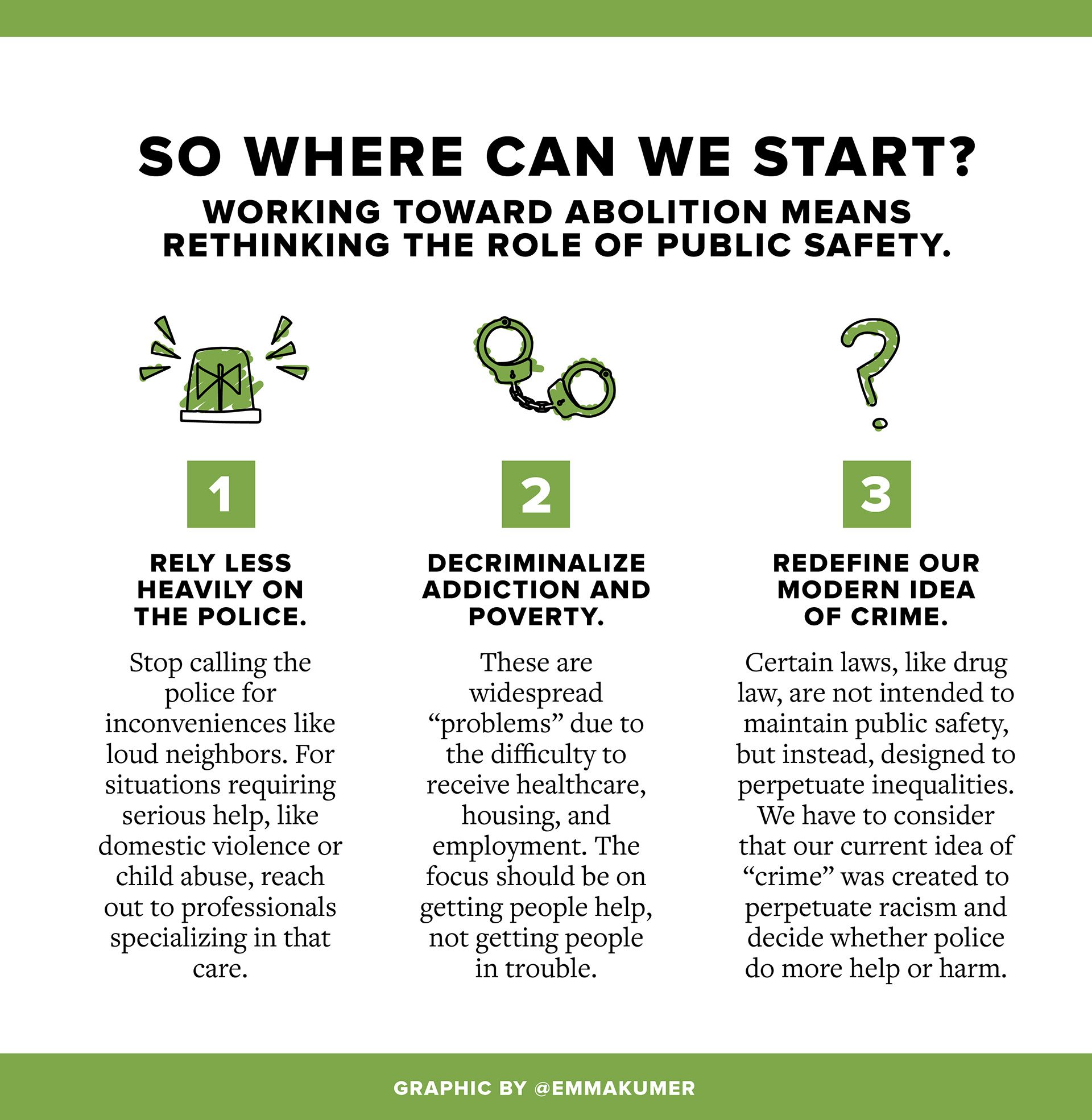

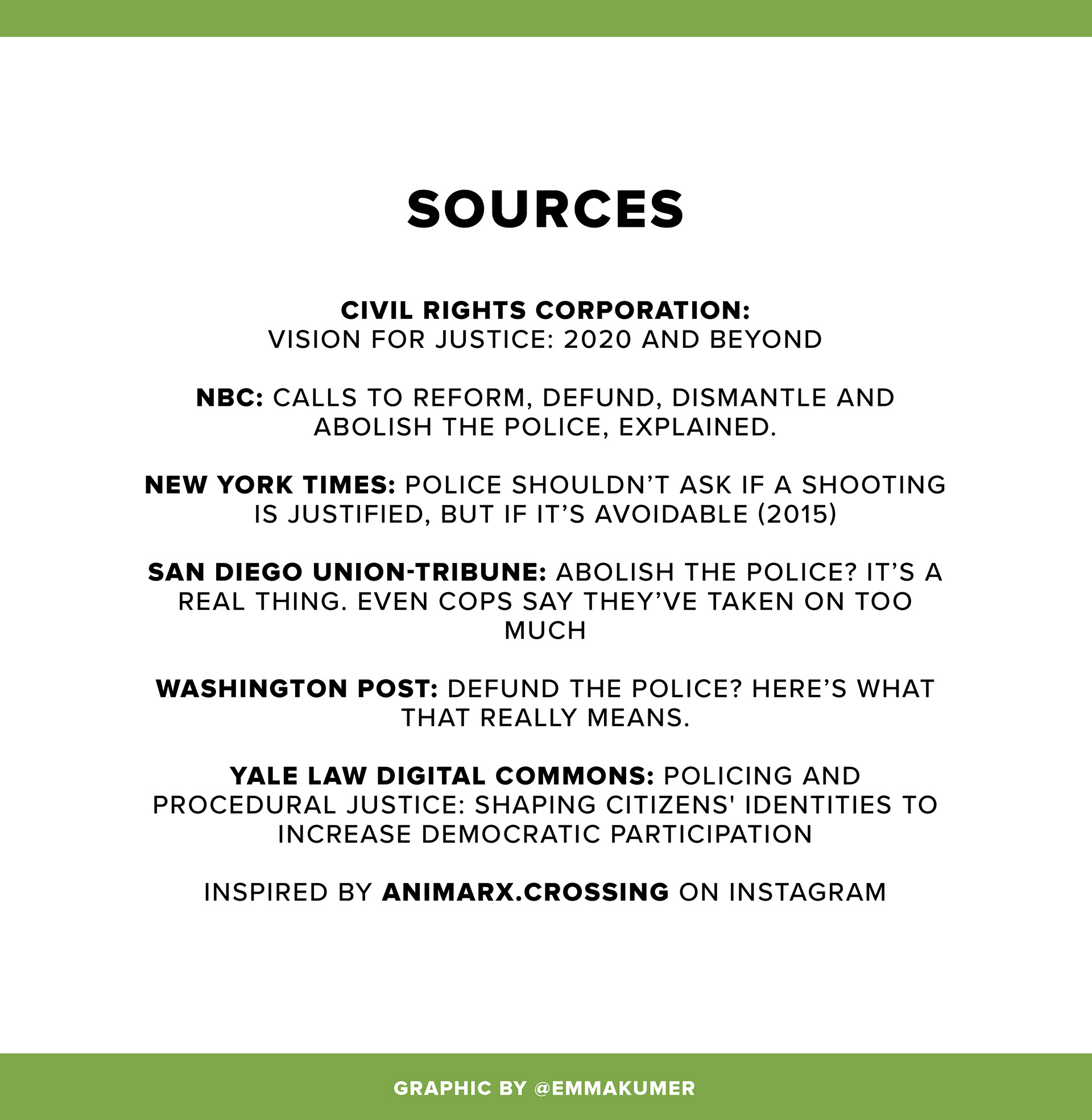

I studied their posts until I could reverse-engineer them. The ideal Instagram infographic, I told myself, had three things in common: action items, fact-checked information with cited sources, and the perfect balance of text — enough to provide some service, but not so much as to overwhelm.

But not all of the graphics were well done.

As quickly as they had appeared, these informational slideshows became a target for critique. Within days, internet discourse deemed the dawn of the “instagram infographic industrial complex.” (Much like the namesake military-industrial complex, this newer phenomenon describes another interconnected relationship where a system is inseparable from those which feed it.)

In Twitter takedown threads, YouTube video essays, and ironically enough, Instagram posts, the comments were endless — and founded in understandable frustration. Some felt that Instagram infographics oversimplified complex issues. Others noted that they spread misinformation. (And they did: viral graphics claimed that the police officers who killed Breonna Taylor had been at the wrong house; formal reports of the event confirmed this was actually not the case.) Some critiqued the design, for appearing too corporate or, inversely, jarringly cutesy. But the biggest critique was that these sharable bites of audience-friendly activism were just a way to feign interest, a salve for the guilt of doing nothing. They were the latest mutation of performative activism — or, more colloquially, “slacktivism.”

I posted five infographics in a row to Instagram. For two months I had been pulling all-nighters, meticulously fact-checking and researching each graphic, to create social media content outside of my 9-5 job. I found it inspiring and engaging in the moment, but after I pressed “send,” I was consumed by fear, opening the Instagram app every four minutes to check for hate comments and angry DMs. I grew more and more anxious that people would think I was only doing this to gain more followers or make myself look like a “good person.”

This wouldn’t have been a genuine fear unless, deep down, it was a little bit true.

A Moral Arms Race

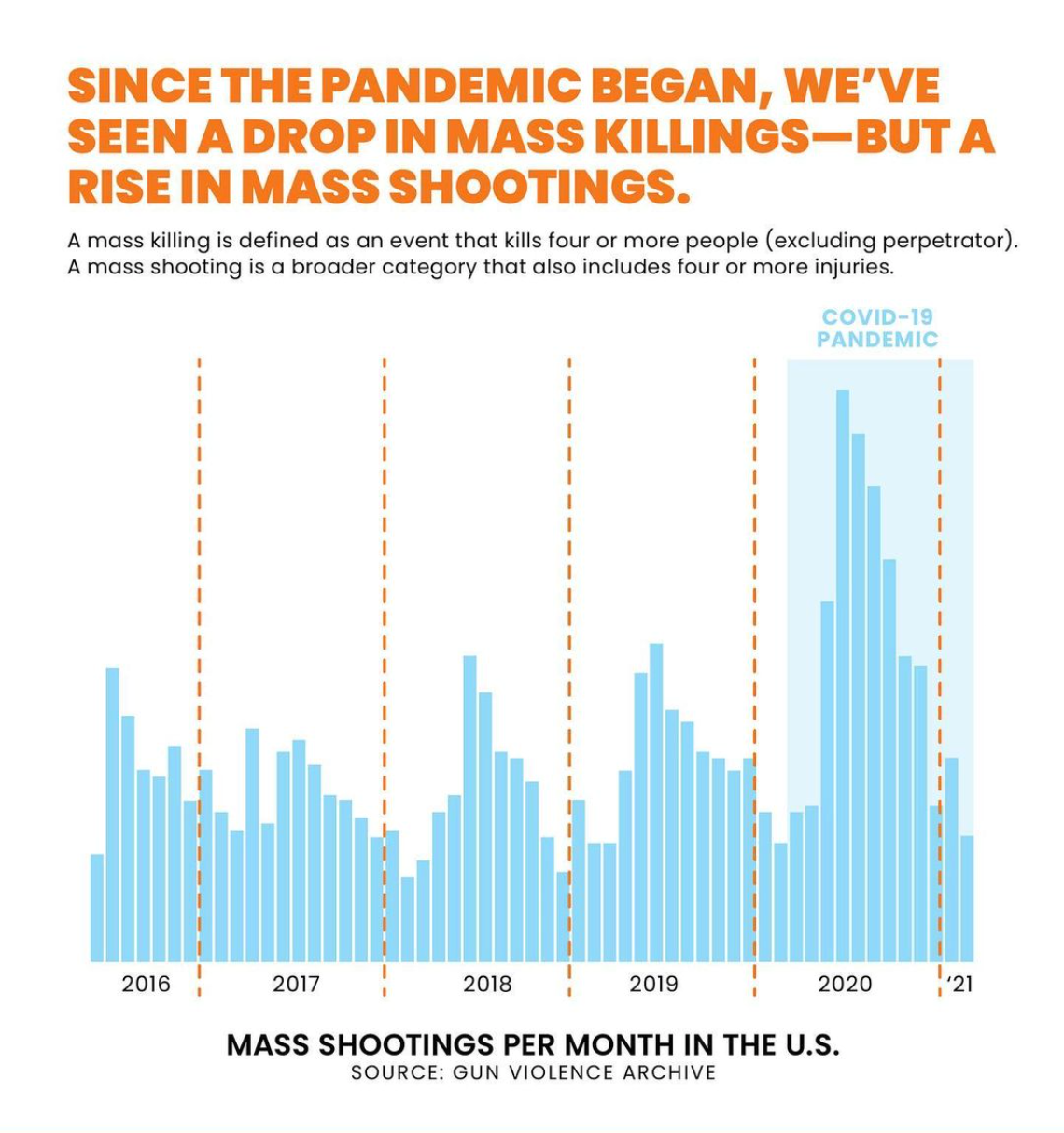

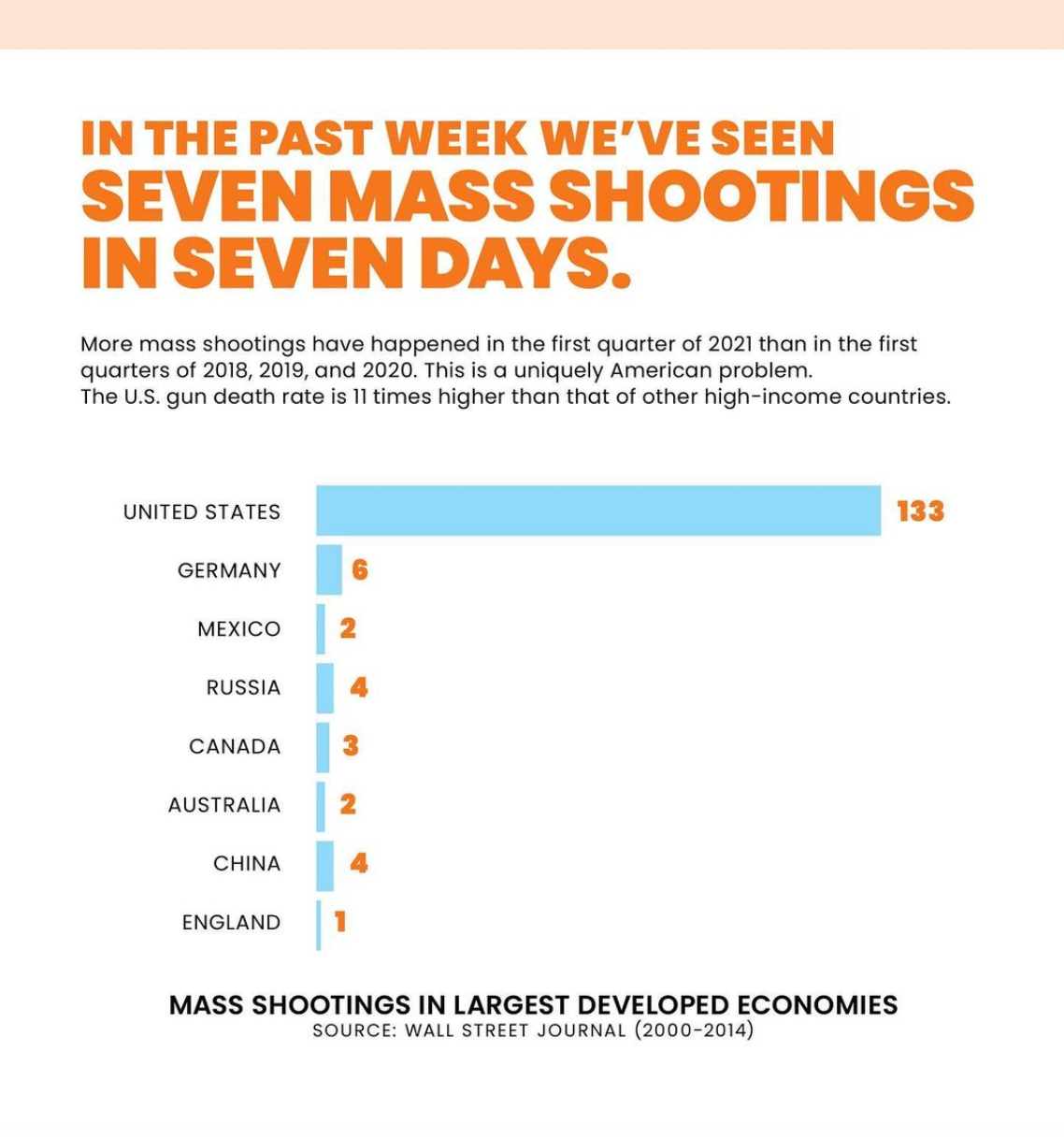

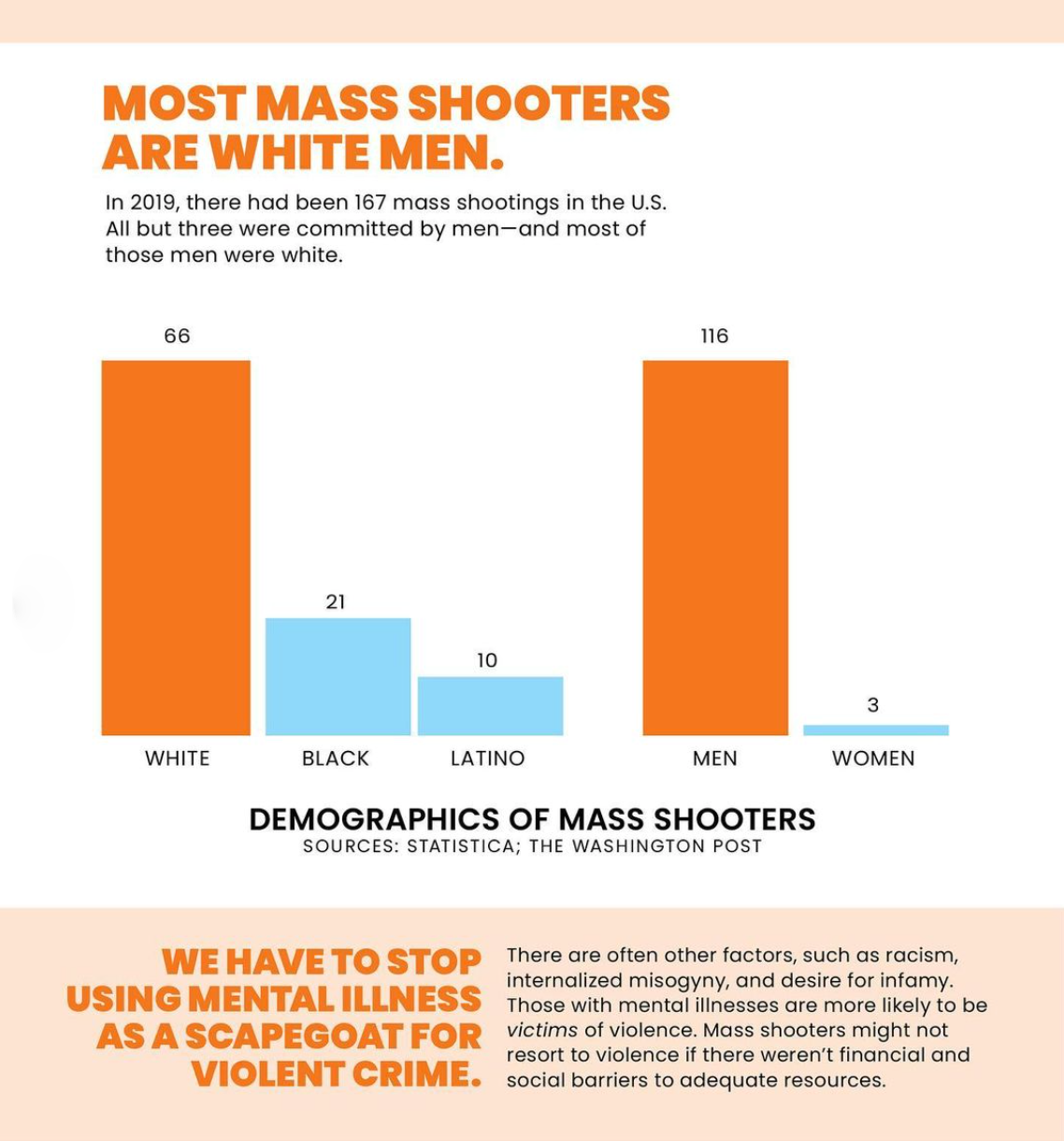

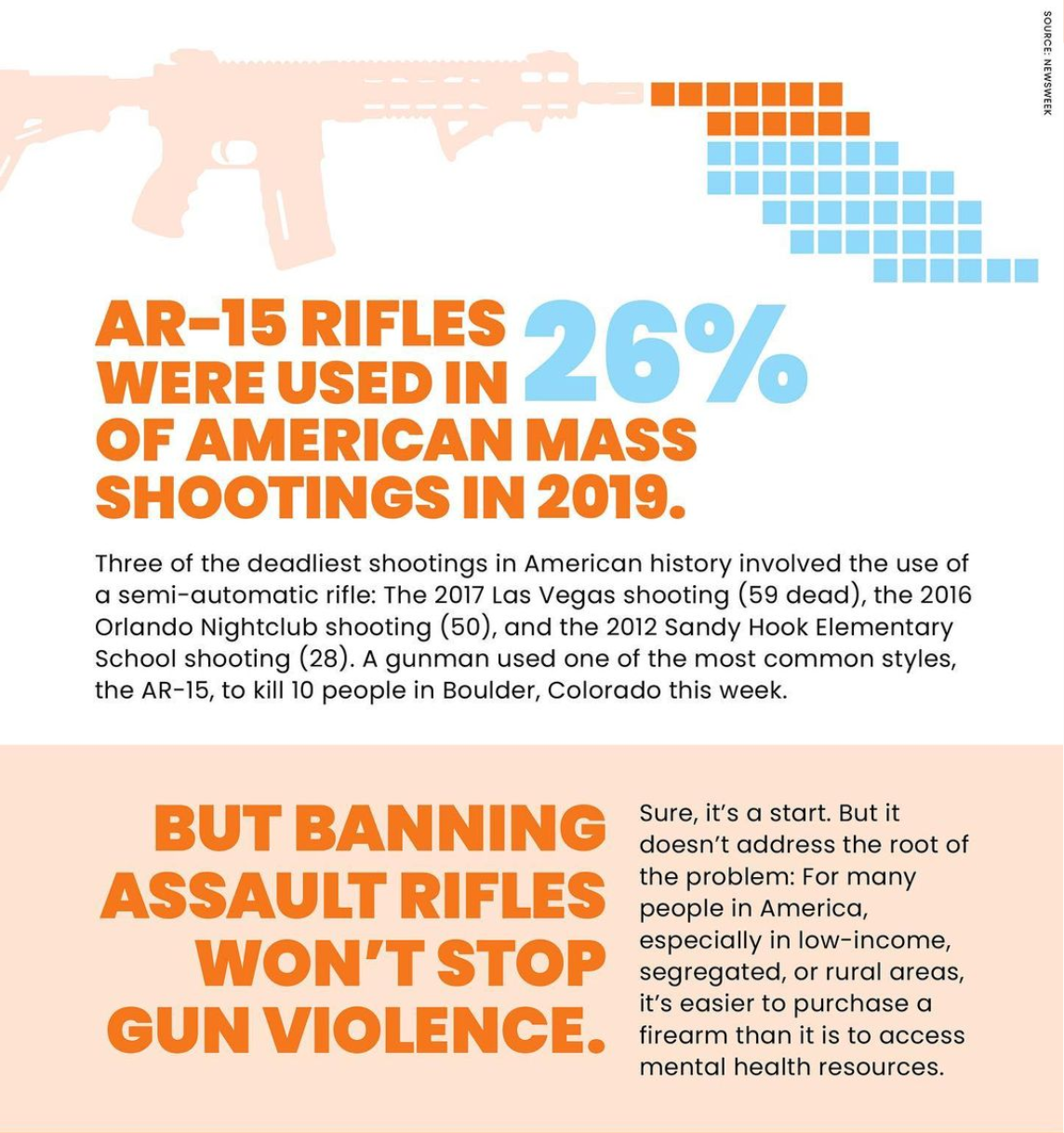

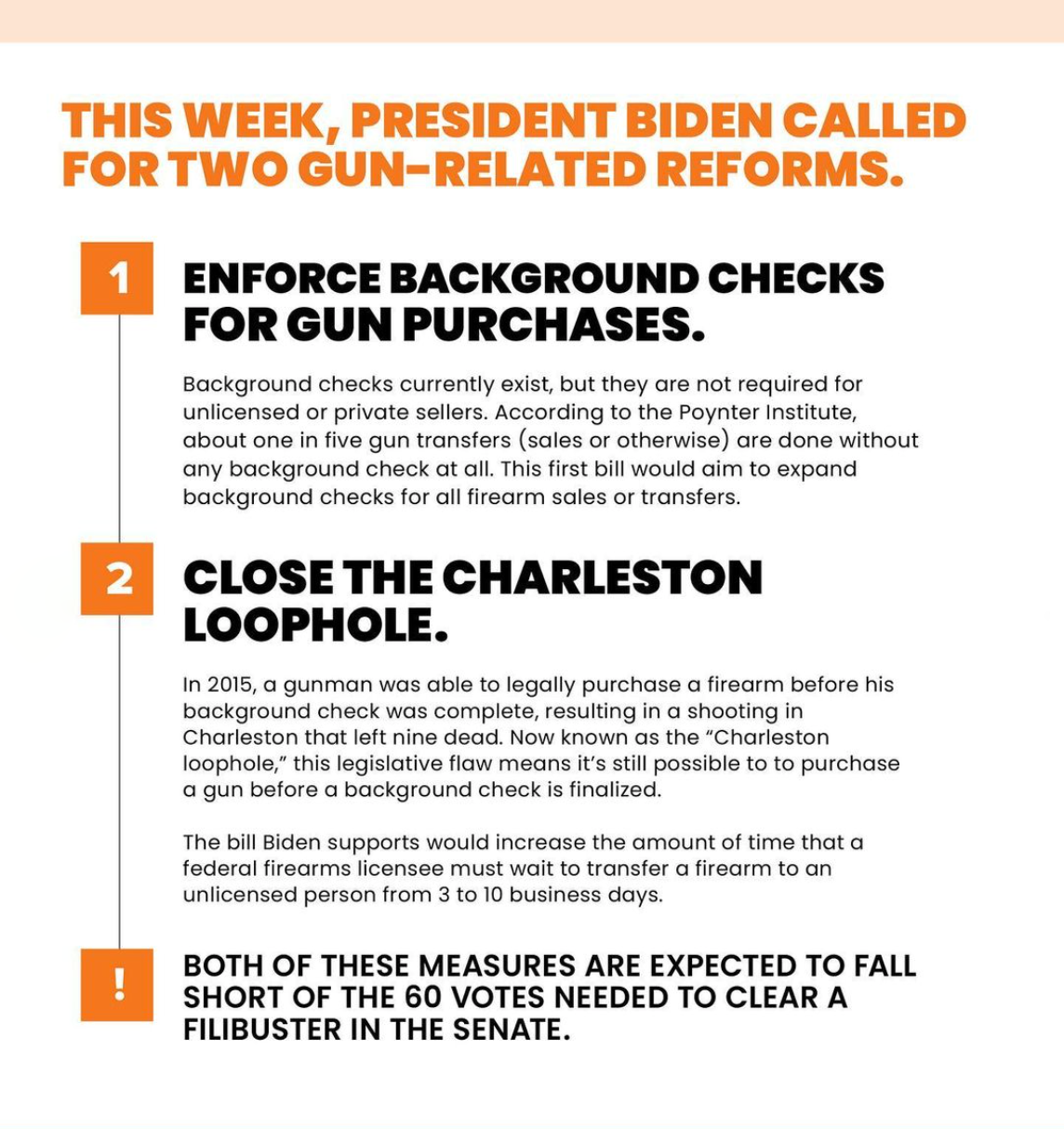

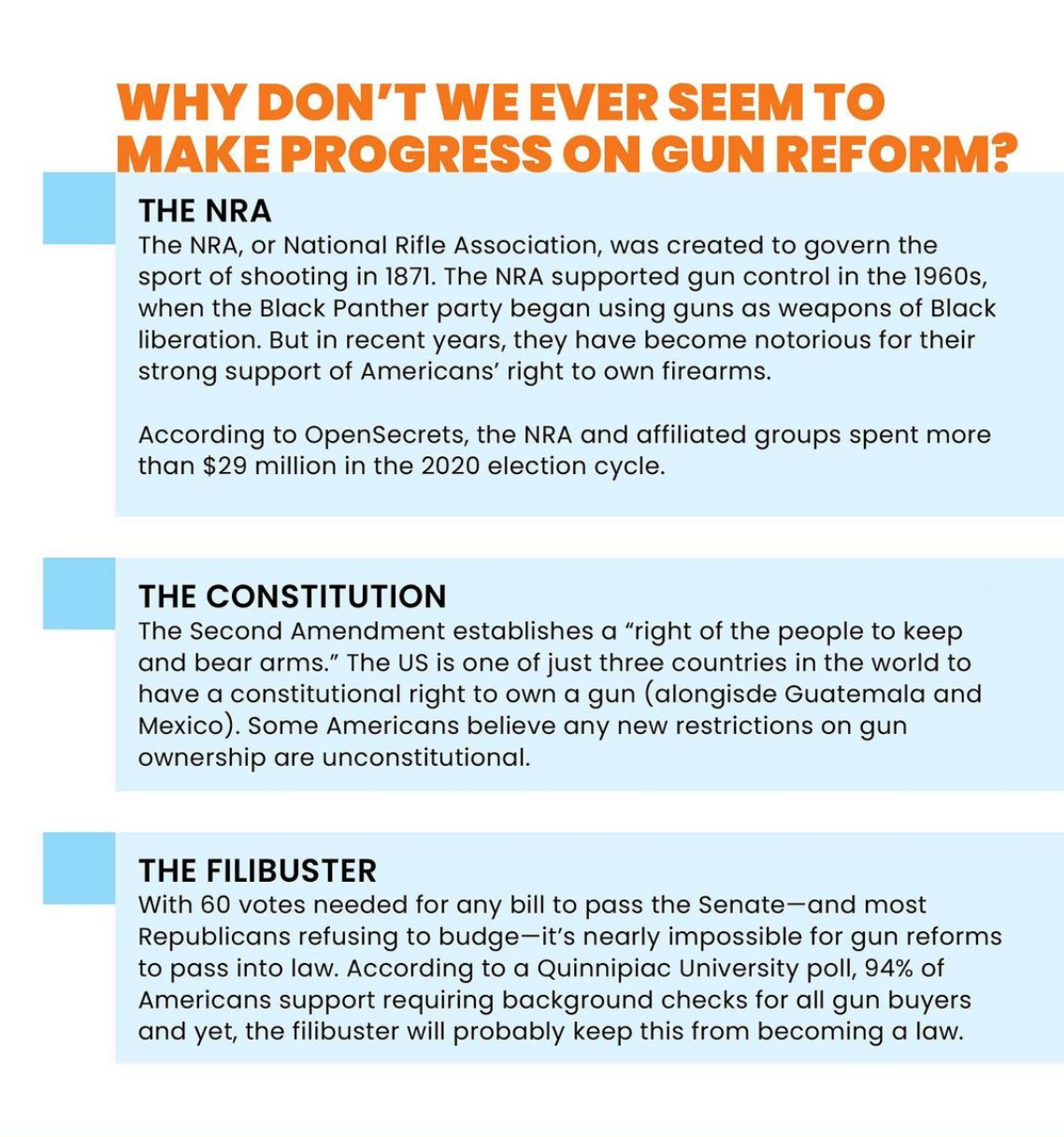

Over two years have passed since the death of George Floyd, and despite heavy criticism, Instagram infographics have not disappeared from the platform. In fact, they’ve become a mainstay every time a major world event occurs. After Black Lives Matter, the infographics tackled voter suppression. Mass shootings. Climate change. Asian hate crimes. The Israel/Palestine conflict. More mass shootings. The fall of Roe v. Wade.

“I have started measuring the impact of a global atrocity by how many people post on their stories about it,” one of my former roommates quipped, once, on FaceTime.

“How does that make you feel?” I asked.

“I mean, it’s weird, right?” She paused. “When everybody is doing that, I feel like I have to as well. I don’t want anyone to think I don’t care.”

This isn’t even an irrational fear. I conducted an informal poll on my Instagram story (naturally) and found that 32% of my followers said they judged their friends for being silent on certain issues. After Roe v. Wade was overturned in June 2022, I saw a lot of people retweeting the same truth: “I am taking note of which of my friends were silent on Roe v. Wade and you better believe every other woman is too.”

“Because I report on stuff like this for work, people expect a certain type of content from me. At this point, I honestly feel pressured to share about traumatic events so that I don’t look disengaged,” A fellow journalist confided to me. “I feel like social media can be a good way of raising awareness, but like, what does me and 16 other friends reposting the same thing do?”

The consensus seemed polarized on two sides, with most people seeing both the apex and nadir of potential. At its worst, you can view social media as “A major tragedy is occurring. How can I make this about me?” and its best, you can view social media as “We all get a space to shout something into the void. And if enough of us shout the same thing, other people might notice.”

On the surface, the proliferation of these graphics expresses our desire to show support in light of tragedy. But beneath, it touches on a very human desire to be perceived as good people. And on top of that, to look like good people who don’t have to try, good people who just are.

To make the action of posting on Instagram stories look less like virtue signaling, it’s become commonplace for people to provide tangible proof of caring in addition to their story shares: snapshots of protest marches, Black justice book covers, screenshots of donations. But it is, inherently, a performance. Social media is a million tiny acts of self-definition.

Are we doing anything?

A couple weeks after my first graphic went viral, I got a direct message from a stranger. My inbox was flooded with DMs ranging from thankful to combative, but this one in particular stood out to me.

“You made a typo,” It said.

I went back and the letters jumped out at me. Not only was it a typo, it was a major error: I had misspelled Ahmaud Arbery’s name. In the resulting ache of guilt, I realized something else: 12,000 people had “liked” the post and only now, a week later, was someone telling me about this egregious typo. Occam’s razor could suggest that most people weren’t reading the post at all.

The ongoing conversation about Instagram activism boils down to a discussion of whether or not the performative nature of social media can ever be harnessed to catalyze real change. It asks if these apps can be tools to educate and unite rather than deceive and divide.

Some days I think it’s all in vain. The fast-paced nature of social media reduces any thought to a mere blip and each post is just another pointless act of rebellion minuscule beside the vast monstrosities incurred by the giants who rule society. But other days I wake up and feel nervously optimistic that the phone in my hand comes with the power to make a difference. I think I believe this, in part, because I have to. I have to believe social media can be a tool for good, or I’d have to admit that I was raised with one foot gradually sinking deeper into quicksand we created ourselves.

I like to think that the good and evil in social media can coexist simultaneously: We know that social media sometimes calcifies the most bitter characteristics of humanity. That its users will share false information or share without stopping to double-check. That people will form camps based around harmful theories or block accounts who disagree with them until their feeds are echoes of accord. But it is also true that my group of friends can use social media to raise $7,000 for Black Lives Matter overnight. That I can find Facebook Events for fundraising events in my neighborhood. That, within two clicks, I can find a PDF of the Los Angeles Police Department budget. That I can access countless news articles and research papers about the causes I care about. That I can teach people who have never met me to do these things, too.

In my conversations with my Instagram followers, they offered advice for making Instagram stories more meaningful.

• Don’t passively share: Start a conversation with your followers by offering your own thoughts on a topic.

• Lead by example: Give an example of how you are going to make a difference (calling your representatives, donating to a particular fund) to reduce barriers for others to do the same.

• Think before you post: Withhold footage of graphic violence or potentially triggering information.

Posting on my Instagram story now has become a practice of self-reflection. I ask myself, why do you want other people to see this? Maybe I want to look more informed, because I have imposter syndrome working in journalism. Maybe I want to be rewarded for kindness. Maybe I’m just 24 and self-centered and eternally online and it feels dishonest not to share every event that impacts my day. But a part of me also posts because it forces me to engage with the material and educate myself. A part of me posts so that I can spark conversations with friends and have more meaningful discussions about what is going on in the world. The theory of psychological egoism states that there is no such a thing as a purely selfless action, and I think this is even more true on the Internet.

On my most optimistic days, I can imagine that it makes a difference to you.

Maybe, your first step is engaging with a friends' post by re-sharing it on your feed. Maybe you’ve never posted something political before, and this scares you, but then you witness the support of one or two other people and feel empowered to do it again. Maybe next time, you add a paragraph about what the event means to you, and enough people respond in agreement that you figure you should do something. Maybe you post again, asking for people's Venmo usernames, because you’re going to make a donation. And it started with a dumb selfish action, but all of a sudden, you’re giving $200 to a charity you didn't know existed last week. This weekend you might attend a protest. Tomorrow at dinner you’re educating your family members when they make an insensitive comment. Next week you’re informing your friends about issues they might know about and you’re supporting political candidates who might be in a position to make an impact. And if every person in the world starts on this path with you, eventually, we’ll be different people.

All of this runs through my head as my finger hovers over the screen. If the potential for positive reasons outweigh the negatives, I hit “share.”

When it comes to sharing infographics, specifically, I now view them as a promise. If I care enough to post, I should care enough to do something in real life. It’s not enough to take part in passive actions like signing random petitions and reading articles. I have to make it a priority to devote time outside social media. Instead of asking, “have I done enough?” I have to start asking, “how can I do more?” and, subsequently, “how can I make it easier for other people to get involved, too?”

And if I live my life like that, maybe I won’t have to worry so much about other people thinking I’m a good person. Maybe, just maybe, I will be.